When a Restraining Order Becomes a Weapon

ZeroDarkTony’s restraining order petition looks less like protection than a tool to silence and harass victims.

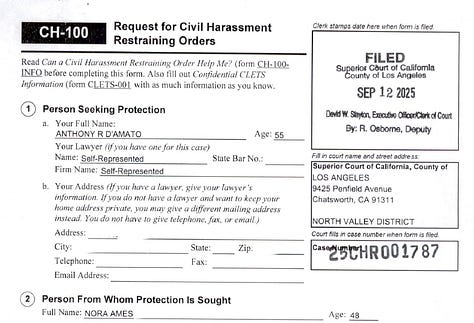

On September 12, 2025, Anthony R. D’Amato — better known online as “ZeroDarkTony” — walked into Los Angeles Superior Court and filed a civil harassment restraining order against Nora Ames, an Oregon-based content creator and, like many of his chosen adversaries, a former Scientologist. In doing so, he continued a familiar pattern for anyone who has followed the darker edges of his feuds: transforming conflicts he himself provokes into courtroom battles where he recasts himself as both a victim and a hero.

The case file illustrates how harassment laws — written to shield genuine victims of stalking and abuse — can be reinterpreted as tools of retaliation. Placed beside D’Amato’s own live-streamed monologues in the days immediately before the filing, the picture grows even more troubling: the courtroom petition appears less a plea for protection than the continuation of a performance already underway online.

A Petition That Reaches Beyond Protection

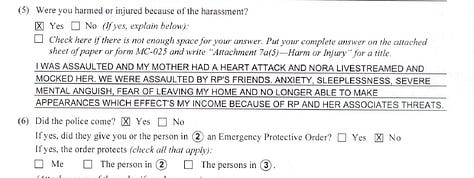

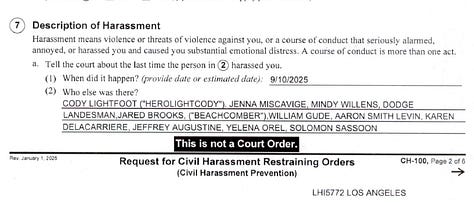

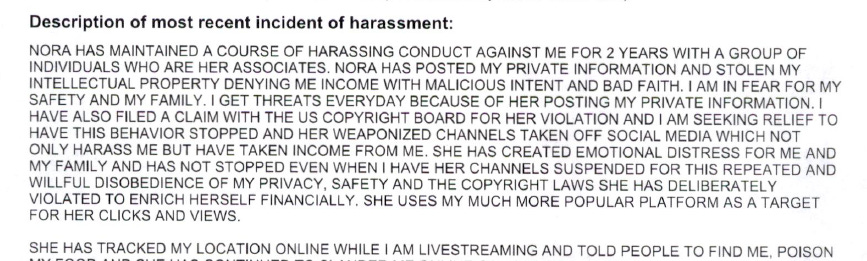

In his petition, D’Amato portrays Ames as the architect of a two-year campaign of harassment. He alleges that she doxxed his personal information, encouraged restaurant workers to tamper with his food, mocked his elderly mother’s heart attack outside a courthouse, and smeared him with labels such as “pedophile” and “anti-trans.” In his telling, she is not just an online antagonist but a figure whose actions have harmed him.

He does not stop there. When answering the form question, “Who else was there?”, D’Amato names a dozen others as Nora’s supposed “associates,” ranging from ex-Scientologists to YouTube critics. The list includes me (“HeroLightCody”), Jenna Miscavige, Mindy Willens, Dodge Landesman, Jared Brooks (“Beachcomber”), William Gude, Aaron Smith Levin, Karen Delacarriere, and Jeffrey Augustine — a bizarre catalog of people he casts as witnesses. He even went so far as to name a minor and his own mother, individuals he is barred from referencing under a standing restraining order. Whether the court treats that inclusion as protected petitioning or retaliatory misuse, it underscores how D’Amato deploys legal filings not simply to seek protection but to continue his fixation through official channels. The effect is to widen the circle of accusation until ordinary criticism becomes, in his telling, a conspiracy against him.

The relief he seeks, however, extends well beyond the protections available in civil harassment cases. Alongside routine “no contact” and “stay away” provisions, D’Amato asks the court to prohibit Ames from mentioning him online “in any way,” to bar her from using nicknames or coded references, and even to prevent her from attending his other court hearings unless subpoenaed. Such demands approach the territory of prior restraint — a measure the American legal system has long regarded with deep suspicion — and they underscore his true ambition: to enlist the courts in silencing her speech, not simply to ensure his safety.

“Prior restraint” refers to an order that prohibits speech before it occurs. American courts have historically treated it as one of the gravest threats to the First Amendment, allowing it only in extraordinary circumstances such as genuine national security concerns or direct incitement to violence. To extend that doctrine into the realm of YouTube quarrels is to ask the judiciary not merely to protect against harassment but to police expression itself — a line the law has long resisted crossing.

The irony is hard to miss. D’Amato has long fashioned himself as a self-styled martyr for the First Amendment, insisting that his crude attacks — including sexual remarks about a minor — were constitutionally protected. Yet now, facing criminal charges and reputational fallout, he turns to the very system he once defied, asking it to silence critics who dare to speak his name in anything but praise. The shift is telling: the man who once waved the banner of free expression to shield his own conduct now invokes the courts to muzzle others. In seeking prior restraint, he is not defending constitutional principle but bending it to his convenience.

The Performance Before the Filing

What makes the filing remarkable is not only what it seeks, but when he filed. In the very days before petitioning the court, D’Amato broadcast hours of live content in which Ames was his central theme.

Across multiple streams, he spoke to her directly in the second person, as though she were present, keeping her alive as a character in his ongoing performance. He called her a thief, a liar, a terrorist. He promised YouTube would erase her channel. He lapsed into pseudo-legal lectures on copyright and fair use, casting himself as the aggrieved rights-holder. And when the legal posture ran thin, he pivoted to vitriol — mocking, taunting, and escalating hostility.

This was not an isolated outburst but a pattern. Week after week, D’Amato returned to her, sustaining a fixation that blurred the line between online commentary and personal obsession. His antagonism was not confined to words. He produced and displayed sexualized images of her, digitally altered to depict her in lingerie, with a blacked-out penis superimposed. He boasted in degrading terms about her child, using his name, invoking sexual violence and death, even tying their faces to “cum-towels.” He wished she would self-harm and made threats of physical harm. Such acts go beyond insult. They are performative humiliation, designed to strip away dignity and to paint her as an object of ridicule before an audience that jeered along. They are attempts to instill fear.

His viewers played a role in this theater. One suggested that a restraining order would be “easy” against Ames. Another spelled out racial slurs in the live chat. The streams became echo chambers in which grievance, legal threat, and abuse reinforced one another, with the creator orchestrating the tone and his followers amplifying it.

By the time he walked into court on September 12, D’Amato had already staged the trial in his head. The courthouse was simply the next act in a drama where he was both playwright and star — recasting himself as the victim, while evidence of his own harassment lay in plain view.

What It Means for the Respondent: The Cost of Defense

For Ames, this is not just a piece of paper. She becomes not only the villain of his streams but the defendant in his case — compelled to respond to allegations that stem less from evidence and more from his ongoing fixation.

Even if the court trimmed back his demands, it still issued a Temporary Restraining Order and scheduled a hearing. She must still respond. She must appear and defend herself. If she doesn’t, she risks a default judgment — and the lasting stigma of public records alleging conduct she denies.

And because D’Amato’s filing fees were waived, and because he can file these actions without an attorney, the cost is asymmetrical. He pays nothing to escalate; she pays in time, stress, and reputation. He knows this well from his many years of courtroom battles. The imbalance allows him to treat the courthouse as another broadcast venue, while Ames shoulders the burden of defense.

Now Ames is raising $50,000 to fund her defense — a figure that may seem extreme at first glance, but is not without precedent. In a minor’s case against D’Amato earlier this year, his attorney filed a motion seeking over $37,000 in legal fees. For Ames, who lives out of state, the costs of travel and potentially additional hearings only add to the burden. D’Amato is well-practiced at delay and continuance, tactics that drive up legal bills and prolong the stress. And should she choose to go on the offense and file her own defamation suit or restraining order, she’s facing another set of court dates and legal expenses. Seen in this light, the estimate is not inflated — it seems to be the right ballpark.

After the Filing

If the restraining order were truly about protection, one might expect D’Amato to step back, let the court speak, and move on. Instead, the filing became fresh content. In the days after September 12, he continued to center Ames in his broadcasts — mentioning her more than a hundred times, dissecting the case for viewers, and keeping her fixed as his antagonist. Even after filing the RO, she remains a constant subject — proof he didn’t actually want any separation.

He even elevated the feud into politics by comparing himself to conservative commentator Charlie Kirk. “I am Nora’s Charlie Kirk,” he declared on stream, recasting his restraining order not as a private dispute but as a public stand. In his telling, Ames was not just a critic but a representative of a broader mob out to silence him, and his trip to court was proof that he was the persecuted truth-teller. This comparison inflates his sense of importance while casting Ames as an organized, political-level enemy.

Court filings and restraining orders became talking points, folded seamlessly into his online persona. He narrated the legal process as though it were a serialized drama, boasting of his petition while simultaneously continuing to taunt and insult the very person he claimed to fear. The contradiction was striking: having asked the court to silence Ames, he kept her alive as a character in his show. The restraining order did not end anything — it opened a new chapter, one where the government itself becomes a player in his performance.

The Broader Problem

Restraining orders are crucial when there is genuine danger. But when they’re misused, they shift the burden onto the innocent, forcing them to defend against claims rooted more in obsession than fact.

That is what Ames faces now. Whatever the judge decides, the filing itself shows how easily a performance can spill from YouTube into a courtroom, and how the cost of that performance is carried not by the provocateur but by the person he casts as his villain.

Great job breaking this all down!

Thank you for writing this amazing article. And it is an article. Perfectly put. 👌🏻